You probably know IBS can be a pain in the butt. But did you know it can also be a pain in the back, shoulder, or neck? In this article, we’ll explore how messages travel from your gut to your brain and how a fork in the road can lead to referred pain. Grab your spectacles friend, ’cause we’re about to get nerdy!

What Is Referred Pain?

Many members of the IBS community suffer from an issue called “referred pain.” This is when pain from one part of the body (like the gut) is felt in a different part of the body (like the neck, shoulders, or lower back). Weird, right?

To understand the mechanics of referred pain, you’ll need to brush up on your nervous system vocabulary. Once you know which parts of the nervous system we’re talking about, I’ll tell you how scientists suspect the magic mischief of referred pain happens.

Wondering where pain can be referred to in the body? Check out this handy referred pain map. This will help pinpoint where you feel that sensation of pain whenever it arises.

Meet Your Nervous System

Your nervous system is made up of thousands of nerve cells called “neurons.” These neurons connect sensory receptors all over your body to your brain. Think of them like telegram wires connecting different regions of your body to a command center.

Because the nervous system can be a confusing place to navigate, in this article we’ll focus on the key players in referred pain: Your Central Nervous System (CNS), Somatic Nervous System (SNS), and Autonomic Nervous System (ANS).

What Is the Central Nervous System (CNS)?

The Central Nervous System (CNS) is made up of your brain and spinal cord. This dynamic duo sifts through information sent from sensory receptors in your skin, muscles, and organs (like changes in pressure, temperature, or chemical imbalances) and makes decisions about how the body will respond to that information.

Once your CNS has a game plan in place, it sends instructions to the specific parts of the body that will carry out its plan.

What Is the Somatic Nervous System (SNS)?

The Somatic Nervous System (SNS) is your “voluntary” nervous system. It’s in charge of moving your skeletal muscles and joints (your body) and monitoring your skin. Give yourself a pat on the back. The SNS is what controls the movement of your arm.

The nerves in the SNS divide into two types of pathways: The sensory (“afferent”) pathway and the motor (“efferent”) pathway. Think of them like two sides of the highway. But, instead of travelling north and south, they travel to and from the Central Nervous System (CNS).

Somatic sensory (afferent) nerves connect to receptors in your skin and muscles. They collect information about your surroundings, your body position, and general information about your well-being (like pressure, temperature, pain, etc.) and send it to your CNS along the sensory (afferent) pathway for processing.

The CNS receives this information and makes a decision about how the body will respond. Once the decision has been made, the CNS sends instructions to the appropriate place in the body using the motor (efferent) pathway.

If you need help remembering the difference between afferent and efferent, remember, it takes effort to move your muscles.

What Is the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS)?

The Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) is your “involuntary” nervous system. It controls the organs found inside your chest, abdominal, and pelvic cavities. Ready to rock your next game of trivia? The technical name for organs is “viscera” – That’s why you can also call the nerves in the ANS “visceral” pathways.

The ANS also divides into sensory (visceral afferent) and motor (visceral efferent) pathways. Similar to the SNS, your visceral sensory receptors collect information about your organs. They send this information to the Central Nervous System (CNS) along the sensory (visceral afferent) pathway.

Once your CNS receives this information, it decides what actions to take and sends instructions to the appropriate place using the motor (visceral efferent) pathway.

Heads up! The sensory pathway of the ANS is still a bit of a mystery to scientists. But, we know it is one of the key culprits of muscle pain or myofascial pain.

How Messages Travel from the Body to the Brain

Now you know your Somatic Nervous System (SNS) and Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) bring sensory information to your Central Nervous System (CNS) along sensory (afferent) pathways; and that your CNS sends instructions back to your body using motor (efferent) pathways. But, how do messages travel between the body and the CNS?

The way your SNS and ANS integrate into your spinal cord can be tricky to understand. What you need to know to understand referred pain, is that your SNS and ANS travel side by side through spinal roots that create a bridge between your body and your spinal cord. This takes place with 31 pairs of nerves, each of which serve specific muscles and organs in your body. When they’re working properly, these nerves branch out to connect every inch of your body to your CNS.

Along with serving specific muscles and organs, each pair of nerves also serves a specific region of your skin. These regions are called “dermatomes.” Each pair of nerves serves a specific dermatome (though, most regions overlap a little). This creates a specific pattern of sensory nerves serving your skin. Check out this dermatome map for an idea of what each region looks like.

How Does Referred Pain Happen?

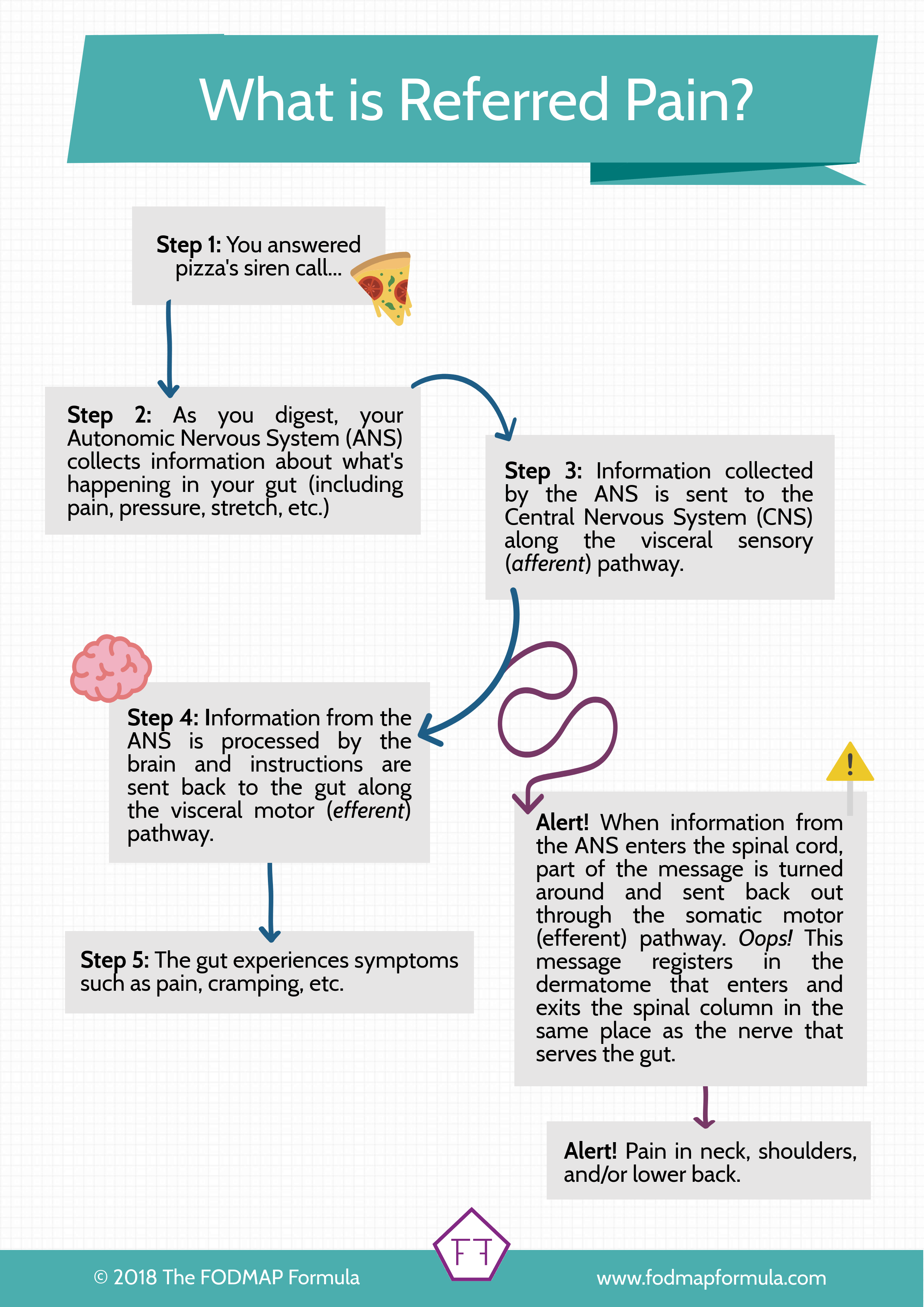

Ready to put all this information together? Great! Imagine you indulged in the most epic slice of pizza. Your taste buds were pretty excited, but now your tummy is not impressed. You’re starting to get cramps, maybe some gas, and you have a nagging pain in your left shoulder. Wait, shoulder pain? What happened?

Understanding the Jump

When you experience gut pain, the sensory receptors in your intestines collect the pain message from your gut. This message travels to your Central Nervous System (CNS) along the sensory (visceral afferent) pathway.

When the message reaches the roots of the spinal cord, it enters the CNS like any other message. But, in the case of referred pain, something unexpected happens and part of the message is turned around and sent back out of the spinal cord along the somatic motor (efferent) pathway.

Since the Somatic Nervous System (SNS) carries messages about the body, not the organs, the message travels to the dermatome that enters and exits the spinal cord in the same place in the spine. The message “I’m in pain” registers in that region of the skin. For IBS patients, this looks like pain in the neck, shoulders, or lower back. Weird right?

Guess what! You probably already know an example of referred pain > this is the same reason you feel pain down the left arm during a heart attack! The dermatome that serves the left arm enters and exits the CNS in the same place as the nerve that serves the heart.

Where Can I Experience Referred Pain?

This is a complicated question! The first thing you need to know is that referred pain can only travel to the dermatome that enters and exits the spinal cord in the same place as the nerve of the organ in question. Since the large intestine is served by several distinct nerves, pain related to your large intestine (the home of IBS) may be referred to your neck, shoulders, or lower back, specifically.

I’ll discuss each of these nerves in detail in a future article, so keep your eyes peeled for more information coming soon!

How Do I Know My Pain is Referred Pain?

There are lots of reasons you may feel pain in your body. Especially during a flare-up. Because of this, if the pain is a new symptom or is happening at a different level of intensity, you should always double-check with your doctor. Your doctor can also help you tell the difference between IBS-related pain and other sensations of pain that may feel similar but need medical attention.

Final Thoughts

That was a ton of information, so let’s summarize. Referred pain is a common complaint in the IBS community. It happens when pain signals partially redirect from your organs to your Somatic Nervous System (SNS) as they enter the spinal cord. This causes the pain signals from your organs to register in the skin in another area of the body (like the neck, shoulders, or lower back).

This mix-up can only occur with nerves that enter and exit the spinal cord in the same place. This means, for IBS patients, true referred pain is limited to the neck, shoulders, and the lower back.

I hope this post answered some of your questions about referred pain. If you like this article, make sure to share it using the social media buttons below. Together we’ll get the low FODMAP diet down to a science!

If you like this post don’t forget to share it! Follow me on YouTube @flipyourleaf for a ton of videos on understanding FODMAPs, IBS mechanics, and how to feel safe in your body. Together we’ll get the low FODMAP diet down to a science!

You might also like one of these:

What Is A FODMAP? Seriously, what the heck is a FODMAP? Check out this article for everything you need to know about what these sneaky little carbohydrates are and why they cause you trouble.

How to Cope with IBS-Related Bloating Sometimes you can do everything right and things will still go wrong. I interviewed the experts for tips on coping with symptoms when our bodies feel out of our control.

How to Survive the Holidays with IBS Worried about keeping your IBS symptoms under control this holiday season? Check out these practical tips on preventing and managing common IBS symptoms.

References

This article was edited by Dr. Anne Agur B.Sc.O.T; M.Sc; Ph.D.

- Agur, A. M., Dalley, A. F., & Grant, J. C. (2017). Grants atlas of anatomy (14th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

- Drossman, D. A., & Chang, L. (2016). Rome IV multidimensional clinical profile (MDCP) for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Raleigh: Rome Foundation.

- Heidelbaugh, J., & Hungin, P. (2016). Rome IV Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders for Primary Care and Non-Gi Clinicians (First ed.). Raleigh, NC: Rome Foundation.

- Marieb, E. N. (2004). Human anatomy & physiology (6th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Pearson Benjamin Cummings.

- Martini, F., Ober, W. C., Nath, J. L., Bartholomew, E. F., Garrison, C. W., Welch, K., & Martini, F. (2011). Visual anatomy & physiology. Boston: Benjamin Cummings.

- Moore, K. L., Agur, A. M., & Dalley, A. F. (2015). Essential clinical anatomy (5th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

- Moore, K. L., Dalley, A. F., & Agur, A. M. (2017). Moore Clinically oriented anatomy (8th ed.). Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Neurovascular Supply of the Large Intestine. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/neurovascular-supply-of-the-large-intestine

- Seeley, R. R., Stephens, T. D., & Tate, P. (2006). Anatomy & Physiology (7th ed.). Boston, Mass: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

- Tortora, G. J., & Derrickson, B. (2012). Principles of anatomy & physiology(13th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- The Vagus Nerve. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/the-vagus-nerve