Your pelvic floor plays a crucial role in your body! So things can get pretty complicated when it’s confused about its job or too weak to get it done. In this article, you’ll get a crash course on your pelvic floor and how pelvic floor dysfunction may impact your IBS. Brace yourself, friend! You’re about to get the scoop on why you can’t poop!

What is the pelvic floor?

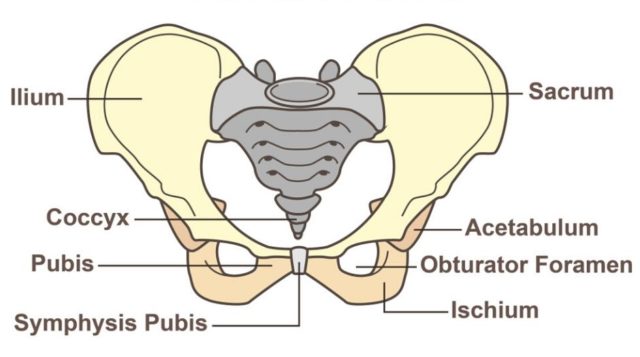

The first thing you need to know is that your pelvis is made up of a ring of bones, including the sacrum, coccyx, and your hip bones. Think of it as a bowl with no bottom. The base of the bowl is called the pelvic outlet and this is where you’ll find the pelvic floor.

The pelvic floor is made of several muscles, tendons, and ligaments that attach to specific places on your pelvic bones. This creates a comfy hammock for your pelvic organs which include the bladder, uterus or prostate, and rectum.

Your pelvic floor is made of three main muscles. The puborectalis, pubococcygeus, and iliococcygeus. Together, these muscles make a muscle group called the “levator ani.” Put those on a post-it, you’re going to need them in a minute!

Depending on what came with your anatomical starter pack, your pelvic floor will also have either two openings (for the urethra and anus), or three openings (for the urethra, vagina, and anus). In addition to supporting your organs, the pelvic floor also helps you consciously control your external urethral and anal sphincters by contracting or relaxing on command.

The pelvic floor is also designed to resist internal abdominal pressure. This helps prevent bladder and bowel leakage when the pressure in our abdomen increases – like when we laugh, sneeze, cough, or lift something heavy.

Before we go any further, let’s take a second to break down each of the pelvic floor muscles, so you understand what they do.

Pubrectalis

The puborectalis is attached to the pubis (the bones at the front of your pelvis) and makes a loop around the rectum. When this muscle tenses up, it pulls the rectum into a bent or kinked position. It is significantly harder to pass stool when the rectum is in this position. So this little kink is essentially a built-in safety mechanism to help us hold in stool until we’re ready to use the washroom.

The puborectalis is tensest when you’re standing and relaxes when you sit down. When you’re ready to “let it go,” the muscle goes slack, allowing the rectum to relax into a straight line during your bowel movement.

Pubococcygeus

The pubococcygeus is a thin muscle that starts at your pubis and attaches to the coccyx (aka the tailbone). This muscle creates a sling or hammock to support the pelvic organs. It also helps elevate and retract your external anal sphincter to help you consciously control when it opens and closes (thanks, but also ew!).

Iliococcygeus

The iliococcygeus is a wide muscle that starts in the lower part of your hip bones (called the “ischium” or your “sit bones”) and attaches to a ligament at the back of your pelvis called the “anococcygeal ligament.” This ligament tethers the iliococcygeus muscle to the coccyx bone.

This muscle helps form the base of the pelvic floor. It can also tense up to give the pelvic organs extra support and help you consciously control the movement of your external anal sphincter.

What is pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD)

To understand how pelvic floor dysfunction works, the first thing you need to know is how we poop!

Understanding how we poop

Pretend last night you enjoyed an epic slice of low FODMAP pizza. While you were sleeping, your pizza travelled through your gut, where the nutrients were extracted and whatever was leftover transformed into poop.

Heads up, your body moves food through your digestive system using controlled muscle contractions called “peristalsis waves.” When the body has reclaimed all the nutrients and water it can, a final peristalsis wave pushes the stool into the rectum. When the stool enters the rectal canal, it triggers stretch receptors that tell our brain we’re ready to poop.

While we wait for a convenient time to use the washroom, the muscles of the pelvic floor are hard at work, making sure our stool stays securely in our rectum.

First, the puborectalis remains contracted around the rectum, pulling it toward the pelvic cavity. This creates a bend or kink in the rectum, making it difficult to pass stool. The pubococcygeus and iliococcygeus muscles also contract, raising the pelvic floor to help keep our external sphincters closed until our brian gives the all-clear.

Once we’ve reached a toilet, we sit down, naturally loosening the puborectalis muscle around the rectum. Then our brain coordinates squeezing the muscles surrounding the abdominal cavity while simultaneously relaxing the pelvic floor.

When the puborectalis muscle becomes slack, the rectum relaxes into a straight line, and the external sphincter opens so the waste can be evacuated.

Understanding pelvic floor dysfunction

I had a lot of questions about pelvic floor dysfunction and how it may impact people with IBS, so I spoke to Laurie Bickerton, a Toronto-based physiotherapist specializing in pelvic floor muscle dysfunction.

Bickerton explained that pelvic floor dysfunction is a functional disorder. This means there isn’t anything wrong with the physical structure of your pelvic floor, rectum, or anus. But they’re not behaving the way we would expect.

This might be because the muscles of the pelvic floor have weakened, the muscles can’t relax the way they’re meant to (either around the rectum or around the external anal sphincter) or, perhaps, a combination of both issues.

What are the symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction

A person suffering from weak pelvic floor muscles may experience bladder or bowel leakage (incontinence). They may also experience organ prolapse, which means the vagina, uterus, or rectum may start to poke out of the vagina or anus. These symptoms may be treated with exercises designed to strengthen the pelvic floor, corrective surgery, or a combination of both.

A person who has overly toned or consistently contracted muscles may experience chronic constipation, a feeling incomplete evacuation, pain in the buttocks, anus, perineum, or around the hip girdle (where your underpants sit around your hips), and possible organ prolapse caused by repeated straining.

Overtonned pelvic floor muscles are often treated with targeted stretches, massage therapy, relaxation techniques, and biofeedback to help retrain the pelvic floor muscles to relax on command. Some types of organ prolapse may also require corrective surgery.

Understanding the role of the gut-brain axis

When asked how pelvic floor dysfunction might impact people with IBS, Bickerton emphasized that pelvic floor dysfunction is more complicated than our muscles’ ability to contract and relax. In fact, treating pelvic floor dysfunction often involves treating people’s minds and lifestyles as well as their muscles.

“There is a theory called ‘multifocal memory,’” Bickerton said, “that suggests our minds tag our memories in different places in our brains. So when we think of cinnamon, for example, it may trigger memories of your grandmother, or baking, or the taste and smell of cinnamon, or how much you miss your grandmother. So cinnamon isn’t just one thing in your mind.”

She suggested we also carry multifocal memories of our physical experiences. So when a person experiences painful bowel movements caused by hemorrhoids, anal fissures, or pain in and around the anus, their brain may tag the memory of evacuating our bowel with pain.

Bickerton went on to say that pain creates especially sticky memories in our minds. Meaning a few bouts of pain can make a big impression on our brain. This may lead people to become hyper-vigilant about scanning for pain during bowel movements or that pain sensors in and around the anus may over-report what they sense.

Repeated straining and bearing down without a successful bowel movement may also produce feelings of anxiety, frustration, and stress, causing the muscles to tighten further.

Situations like these may create a feedback loop of pain causing the pelvic muscles to tense, which creates more pain, etc. Over time, this loop may retrain the pelvic floor to tense up in anticipation of pain when it receives the brain’s signal defecate.

This type of muscle mixup is called a “paradoxical contraction” or “dyssynergic defecation” meaning the muscles are doing the opposite of what they’re designed to do.

According to Dr. Satish Rao, of Agusta University, up to 40% of people who experience chronic constipation suffer from dyssynergic defecation. So if you’re experiencing symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction, schedule a chat with your family doctor or a physiotherapist specializing in pelvic floor health.

How is pelvic floor dysfunction treated?

Unbeknownst to most of us, human beings tend to carry stress-related tension in their pelvic floor muscles, as well as more obvious places like the shoulders and neck.

This means trying to move your bowels after your boss yelled at you, or you were stuck in traffic, or your kid insisted they need a 17th glass of water before going to bed is much more complicated than when we’re relaxed; whether we have pelvic floor dysfunction or not.

According to Bickerton, this is because stress activates the sympathetic nervous system or the “fight or flight response.” She says since most digestive and pelvic floor functions happen during the “rest and digest” stage, people who live in a constant state of stress may be at risk for issues like pelvic floor dysfunction.

Because of this, Bickerton said her treatment plans often involve a relaxation or mindfulness component. The aim of which is to help her clients increase the amount of time per day they spend in the parasympathetic (rest and digest) stage.

This can be achieved in several ways, including daily meditation or mindfulness exercises, restorative yoga, and changes in daily habits, such as increasing physical activity, improving sleep quality, following a balanced diet, and taking a break to relax your body when struggling to move your bowels.

Other treatments for pelvic floor dysfunction may include stretches designed to loosen the muscles of the pelvic floor or massaging the muscles to help them stretch and relax.

Clients also learn techniques like diaphragmatic breathing, the I Love You massage, and to encourage daily habits like thoroughly chewing food to promote strong and consistent peristalsis waves, using tools like the squatty potty to encourage the pelvic muscles into a more relaxed position, and limiting time in the bathroom to prevent excessive straining.

Another treatment option, which is by far the coolest, is biofeedback therapy. According to Bickerton, biofeedback therapy involves using feedback (provided by a machine or directly by your physiotherapist) to let you know when your muscles are contracted or relaxed.

During a biofeedback session, your physiotherapist will walk you through a series of exercises allowing you to consciously relax and contract your pelvic floor muscles. By repeating these exercises, both at home and with your physiotherapist, after a few sessions, your brain should start to provide its own feedback, allowing you to relax and contract your muscles in the correct order without consciously thinking about it. Effectively, retraining your brain!

Final Thoughts

The pelvic floor is made of a group of muscles, ligaments, and tendons called the levator ani which support the pelvic organs, help control our external urethral and anal sphincters, and help us urinate and pass bowel movements on command.

Pelvic floor dysfunction occurs when the pelvic floor muscles become too weak to support the pelvic organs or control our external sphincters, or when the muscles become overly tense, leading to constipation, pelvic pain, and uncoordinated contractions of the pelvic floor muscles.

While there are many ways to treat pelvic floor dysfunction, professionals like Laurie Bickerton believe treatment plans should involve the whole person, including addressing stressors in our daily lives to help keep our muscles relax, making adjustments to our daily lifestyle to promote healthy bowel movements, and non-invasive treatments like biofeedback therapy to help retrain our gut-brain communication.

You might also like one of these:

- How to relieve trapped gas Need some help letting it go? These practical tips will help you prevent trapped gas when you can and relieve it when it strikes.

- Why do your IBS symptoms flare on your period? Have you ever noticed your IBS symptoms always seem to flare up during your period? Here’s everything you need to know about how and why your cycle can throw a monkey-wrench in your gut!

- Is your abdominal pain related to IBS? Have you ever felt a sharp pain or cramp in your abdomen and wondered if it was caused by your IBS? Here’s what you need to know about IBS and abdominal pain!

If you like this post, don’t forget to share it! Together we’ll get the low FODMAP diet down to a science!

References

This article is based on an in-person interview with Laurie Bickerton PT, FCAMPT, AFCI and was edited by Dr. Anne Agur BSc(OT), MSc, PhD

- Agur, A. M., Dalley, A. F., & Grant, J. C. (2017). Grants atlas of anatomy (14th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

- Interview with

- Faubion, S. S., Shuster, L. T., & Bharucha, A. E. (2012). Recognition and Management of Nonrelaxing Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 87(2), 187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.09.004

- Marieb, E. N. (2004). Human anatomy & physiology (6th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Pearson Benjamin Cummings.

- Martini, F., Ober, W. C., Nath, J. L., Bartholomew, E. F., Garrison, C. W., Welch, K., & Martini, F. (2011). Visual anatomy & physiology. Boston: Benjamin Cummings.

- Moore, K. L., Agur, A. M., & Dalley, A. F. (2015). Essential clinical anatomy (5th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

- Moore, K. L., Dalley, A. F., & Agur, A. M. (2017). Moore Clinically oriented anatomy (8th ed.). Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Pelvic Floor Dysfunction Outlook / Prognosis. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/14459-pelvic-floor-dysfunction/outlook–prognosis.

- Tortora, G. J., & Derrickson, B. (2012). Principles of anatomy & physiology(13th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.